Data Acquisition

In an ideal world, you’ll parachute into an organization with a great data platform and pipelines which you can easily access via an API. In reality, your organization may not have a lot of data infrastructure. This means you’ll need to move data from where its current location to the machines where you’ll be using.

How to get data from A —> B

Data can be stored in a cloud environment (AWS, Azure, GCP, etc) or “on premises,” also called “on prem.” “On prem” means the data resides in machines physically located in your building. We generally recommend cloud over on-prem, but you can read more into tradeoffs and determine what’s best for your organization. How you get your data to the cloud depends on which cloud you’re using and where the data currently resides.

Your fundamental questions are:

- How much data do I need to move?

- How far does that data need to go?

- How fast does that data need to move?

The Azure and AWS guides to cloud data transfers provide great information about network (online) transfer and physical (offline) transfer. These websites can provide great information on trade-offs.

Hypothetical Scenario of Moving a Large Dataset

Problem

Let’s say you want to build a computer vision algorithm that identifies objects from images/video taken from an aviation platform. The units that own this image/video data are scattered across the United States, and store this data on local hardware, not a cloud service. You have access to a cloud provider for your storage and compute. How do you get the data from those locations to your cloud?

Our first question is “How much data needs to be moved?” 1 Terabyte (TB) of data is approximately 500 hours of HD video, or 250,000 photos, or 6.5 Million document pages. If you have 10 squadrons that each have 250 video hours per year and 10 years worth of data then you have 10 * 500 * 10 = 50,000 video hours. 50,000 video hours divided by 500 hours per terabyte of data means 100TB of total data, with 10TB per squadron.

Our second question is “How far does the data need to move?” Since you aren’t operating in a cloud-native organization (the DoD … yet), you’ll have to look for offline transfer. Organizations have certainly shipped hard drives across the country before, but 10TB per squadron is too much data to ship on a typical hard drive (not to mention the data may be sensitive or even classified). Instead, you’ll have to look at some of the Azure and AWS (depending on your cloud provider) offerings for offline data movement.

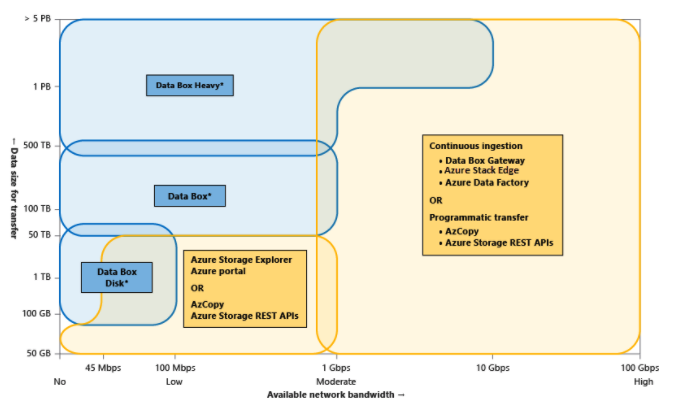

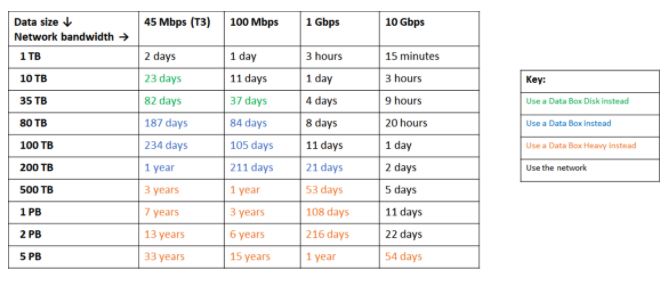

Here is an example of the data size x bandwidth x time calculations from Azure for choosing different online versus offline data movement capabilities like its Data Box.

Azure-specific visual for choosing data transfer capabilities. Source

Azure-specific time table for transferring data. Source

AWS has its own offline movement capabilities, through the Snow family of products (snowcone, snowball, snowmobile). Keep in mind, Snow products and Data Boxes aren’t quite as easy as USB plug-and-play hard drives.

Data Engineering (Basic ETL: Extract, Transform, Load)

You’ve obtained your data and it is stored somewhere accessible. However, it may be in a disorganized format or you may expect to be continuously ingesting/collecting data and updating/improving your analysis. While excels and csv’s are an answer, they’re not a sustainable solution for anything beyond initial research. You should select your data pipeline solution based on the expected longevity (desired scalability) of your project and intended use of the data. The specific architecture of your data pipeline may also vary depending on where you’ve stored your data (e.g. locally, servers, AWS s3, Azure blob). However, the principles remain the same.

Short-term

If the data science solution you’re looking for is just a short term problem –not expecting any (or minimal) updates to your data/solution, it is more expedient to skip the majority of ETL practices/tools. Storing your data in its raw format prior to pre-processing (pre-pre-processing aka pre-data munging) may be viable. However, if you’re working with non tabular data (e.g. excels vs images), you should make sure your data is in a logical file structure. For instance, if you’re planning on building a classification computer vision model, either have each class in a separate folder or each file include the name of its class. This will allow you to more easily read the data in for pre-processing and analysis. As long as your data is setup in one location with a logical structure, you can then easily apply scripts for downstream processing and analysis.

Medium-term

If you’re working with a problem that may take in new data occasionally or is expected to last for more than a couple months, you may want to invest the time to apply ETL/ELT practices (for those who transform their data later). This means that you may want to write scripts that can transform and database your raw data. Depending on whether your data can be easily tabulated or is highly variable/unstructured, you can hoose a relational (e.g. PostGreSQL) or non-relational (e.g. mongoDB) database, respectively. Databasing will allow you to efficiently maintain and track new data in a format that is easily ingested for data analysis.

Long-term

If you’re trying to build a scalable, long term solution that will require regular big data ingestion or event streaming, you should create a more robust data infrastructure. Rather than just having 10 Python scripts that you take turns running to transform and database your raw data, you should automate the movement of your source data into analysis ready storage. This is where you can apply tools like Apache Spark and Kafka (both are available in AWS and Azure flavors as well as open source). Within Apache Spark you can take data ingests and pass it through a database processing (and even pre-processing/modeling) pipeline automatically. Likewise with Apache Kafka, you can set rules (scripts) to manage and process continuous event (data) streams. One of the key benefits of taking the extra time to build this infrastructure (besides automation) comes into play when assumptions of your data change. Rather than having an error break out mid ingest and potentially lose data, your pipeline will be fault tolerant and could continue processing.

Useful Resources:

Navigation

» Previous recipe

» Next recipe

» About

» Ingredients

» All recipes

» Resources

» Code examples