Understanding your Data

After you defined your problem and acquired some data, you really need to understand the data. This means understanding how it was created, what assumptions and biases are implicit in the dataset, and, most importantly, is the information you are seeking actually present in the data?

Machine learning can give you an answer but no amount of neural network layers and voodoo magic can extract information from a dataset that doesn’t fundamentally have it. For example, a bank wants to use ML to predict which types of previously-rejected loans would have perfomed. They shouldn’t use only their own historical data since it doesn’t contain the information on whether those loans would have perfomed or not. Statistically speaking, the bank is seeking to quantify the effect of some predictors on the perfomance of the loan, given the fact that the loan would have been denied in the past. Their own dataset only provides them information on the relationship for those loans that were already approved (source). In this case, they should seek more outside data.

Always clarify your objectives and make sure you have the correct data to support those objectives.

Structured vs. Unstructured Data

Not all data is created equal, not all data is relevant to your problem, and not all data is usable. You must first understand the structure of your data before beginning your problem.

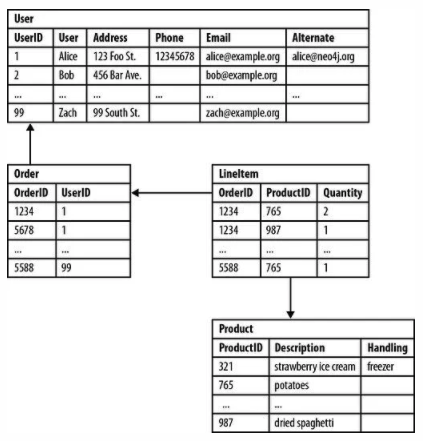

Structured data is often quantitative. It is organized neatly in rows and columns (like a spreadsheet or a table. It may be referred to as tabular data. These data are often stored in .xlsx and .csv files or in relational database. Relational databases can be accessed through Structured Query Language (SQL). An example of structured data may be a list of customers, their addresses, phone numbers, and products they’ve ordered.

Relational databases are great for performing quick searches because they are well-structured. However, this structure can be a detriment. If your data schema (the structure of your database or fields of data collect) changes, your relational database will not easily support this change. Relational databases are also not good for unstructured data.

Example of structured data. Source

Unstructured data is usually not quantitative or easily stored in tables and its fields may change. Examples include comments, images, audio files, video, social media, and text documents (things that don’t fit well in a spreadsheet). These data are better stored in non-relational databases (sometimes called NoSQL databases), which have more storage flexibility and allow you to collect different types of data, but come at the cost of speed of search.

Labeled vs. Unlabeled Data Data

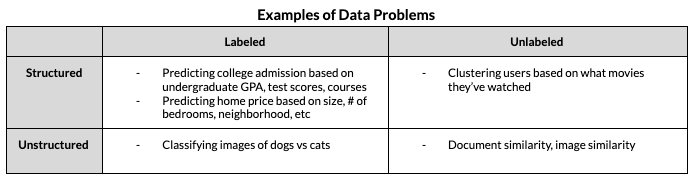

Now that you’ve got data in a database, you need to understand whether it is labeled or not. If you have labeled data, you can do supervised machine learning. If your data is not labeled, you can either label it or do unsupervised learning.

Most machine learning focuses on some type of supervised learning. The general idea of supervised learning is that learning is guided by a teacher who knows absolute truth. For every prediction the machine makes using the training data, there is a label indicating the correct answer. Feedback from these truths allows the machine to learn and then make predictions using future data. Supervised learning problems can be divided into classification (predicting whether this piece of data belongs to one class or another) or regression (predicting a continuous variable like housing price, test score, or temperature). Labels can come in the form of a filename, a column in a spreadsheet, or a folder where you keep all the data of a certain type.

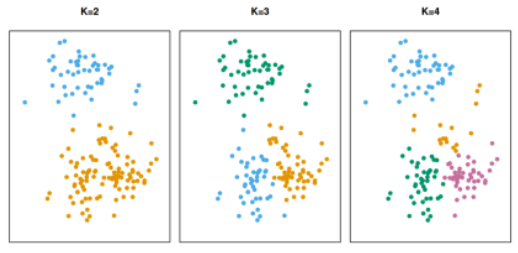

If the data isn’t labeled, or you’re more interested in clustering and similarity than prediction, unsupervised learning can help. Unsupervised learning is often less about finding the “right answer” and more about trying to understand your data. Unsupervised learning is great for clustering similar things (like groups of people based on behavior / survey responses) (example image below). For more information on supervised and unsupervised learning and model for each, see Recipe 8.

Clustering exmple with 2, 3, and 4 groups. Source

Table created by authors.

Data Labeling

For many real world projects you have data but no labels. Data labeling can be one of the biggest bottlenecks in any machine learning project. How you choose to label your ‘ground truth’ data will depend on the expertise required to label the data, the size of the labeling task relative to your team, the system/platform you have to label data on, and how much money and time you are willing to spend on data. Here are a few options:

Do it yourself

Manual data labeling is time consuming and boring but if you don’t have a team of people to help you or much money to spend, it may be the best way to get your project off the ground. Sometimes it’s just you and an excel workbook.

Crowdsourcing

Public Crowd (Mechanical Turk)

Amazon Mechanical Turk is a platform that allows for the crowdsourcing of data sets. It’s relatively cheap on a per-label basis, but labelers are likely not an experts on your problem so their labels may be inaccurate and need to be quality-assured.

Private Crowd

A private crowd may have more training than a public crowd, but costs considerably more. There are plenty of companies that offer this as a service. This is an option when your labeling requires some expertise that is trainable (and you can do quality-assurance on the company’s labels) but the labeling task is still too big to accomplish with your internal resources. Be careful, some vendors may keep your data and the labels for their own use/sales.

Use Subject Matter Experts

If you want the best possible labels on satellite imagery, use trained imagery analysts. If you want the best labels of medical imagery, use doctors. Though expert labelers have the highest quality they often are expensive or strapped for time.

Data Labeling Platform

If you have expert labelers but no efficient way of letting them apply their knowledge to the data, you have a problem. One way to take advantage of your organization’s subject matter expertise is leveraging a data labeling platform. This is basically a software product specifically built to make labeling easier for your experts (more focus on labeling instead of navigating your labeling system).

Labeling Functions

If you have more data than your team of experts can hand-label, one option is to use labeling functions. Snorkel, an open-source project from Stanford, is great for this task. You can use the expert knowledge to write labeling functions that will apply ‘pseudo-labels’ using heuristics. Then, a model is created to learn the accuracies of the labeling functions and reweight/combine/choose among the pseudo-labels to create a single training label per data point. If desired, these pseudo labels can be improved by creating a small set of ‘gold standard’ labels. Snorkel has been used in high-profile research papers in the medical community. Some tutorials can be found here.

Additional Labeling Methods

Transfer Learning

One workaround to tedious manual data labeling or even lack of available data is transfer learning. Depending on the problem, you may be able to use a pretrained model and a few labled examples to get a good baseline model. For example, if you are trying to distinguish between certain military aircraft and you only have a few labled pictures, you can use a large pretrained network such as ImageNet, freeze most layers but the last few, and retrain those layers using your available images. In this case, ImageNet already encodes high-level information in its earlier layers (e.g., shapes, edges), so you can ‘reuse’ this information and tailor the final layers to your specific problem. For more information on Transfer learning, see our Recipe 9.

Hybrid Learning Approaches

If you have dataset with few labeled and many unlabeled datapoints or are interested in self-labeling techniques, here are some more advanced hybrid methods: Semi-Supervised Learning and Self-Supervised Learning:

Semi-Supervised Learning (also known as Semi-automated Data Labeling): If you have already have, or have access to, a performant prediction model for your use case, one approach is to introduce automation into your data labeling workflow by using model inference predictions to form “pre-labels”. Note that these “pre-labels” should almost always be reviewed and adjusted by a human labeler to verify accuracy. There are many ways to sequence this workflow but a simple application is to generate predictions from a single model as an initial labeling stage and route all the outputs to a human labeler for review. The human would then be adding, verifying, or adjusting machine-generated “pre-labels” rather than only applying new labels to raw data.

Self-Supervised Learning: the process of automatically generating labels from unlabeld data by exploiting underlying relationships in the data. For example, in natural language processing, you can hide a part of the sentence and predict the missing words. Or in computer vision, you can randomly crop patches from an image and predict the original position of the patches. More generally, your model learns to predict hidden parts (or properties) from the data. This method opens up your data to more supervisory signals than traditional supervised methods and, as a result, your model learns the underlying representations of images/text. You can then transfer these learned representation (e.g., using Transfer Learning) to the actual downstream task you are interested in (e.g. prediction, detection).

Navigation

» Previous recipe

» Next recipe

» About

» Ingredients

» All recipes

» Resources

» Code examples